If people know who Clara Barton was, it’s most likely because of her service as a Civil War nurse and her efforts in the creation of the American Red Cross. What’s less likely is that people know everything that Barton (1821-1912) did before, during, and immediately after the war. In an unassuming building at 437 7th Street NW, you can learn the incredible story of this historic woman in the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum.

The three-story brick building houses a restaurant on the ground floor, but head through the single door to the side and you’ll find the start of the museum, which leads you up steep stairs to the third level of exhibits. This first level includes a detailed mural noting important scenes from Barton’s life. The opposite wall is filled with gift-worthy items, including Barton quotes on mugs, such as, “I shall never do a man’s work for less than a man’s pay.”

That bold statement came after she said, “I may sometimes be willing to teach for nothing, but if paid at all …” Before she was a nurse, Barton was a teacher and established the first free public school in Bordentown, New Jersey. The school became so successful, Bordentown’s leaders decided it needed a man to run it. Outraged, Barton ceased teaching and moved to Washington, D.C., in 1854.

This is the introduction you’ll hear if you’re able to secure a tour with someone, such as the museum’s education specialist, Michael Mahr. He easily dictates the story of Barton’s life, sharing how her second career was just around the corner at the U.S. Patent Office (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum and National Portrait Gallery), where she was one of the first women to work for the federal government. Barton was demoted (by a man) and earned 10 cents for every 100 words copied. In 1857, James Buchanan won the presidential election and fired his opponent’s outspoken supporters, who included Barton. She left the District and returned to the city and the Patent Office when Abraham Lincoln took office in 1861.

It was then that Barton moved into a 7th Street boarding house, now the museum. Of course she would go to the Civil War’s battlefields, where she would make further history aiding soldiers during active battle. But it’s the next part of Barton’s story that led to this museum, however — a space where she and a small staff processed more than 63,000 requests from people missing individuals who were serving in the war. President Lincoln granted her permission to become an official government correspondent to help find people who had vanished during the conflict, and Barton got to work on receiving letters, publishing lists, and connecting individuals.

She did this invaluable work for a few years until an 1868 visit to Europe, where she would discover the International Red Cross and return home to help found its American counterpart in 1881. Right on brand, during her time abroad, Barton also provided nursing and humanitarian assistance as the Franco-Prussian War raged.

More than a hundred years later, Richard Lyons, an employee of the U.S. General Services Administration, was helping inspect 437 7th Street before the old structure’s looming demolition. As Mahr tells this part of the story (there’s a ghost story component to it), Lyons kept exploring the third floor and eventually discovered enough to reveal how the space had been used, finding more than a thousand objects, including a sign reading “Missing Soldiers Office, Office 3rd Story Room 9, Miss Clara Barton.”

This discovery ended up saving the building from destruction, and in 2007 the National Museum of Civil War Medicine partnered with the GSA to create and run the museum, which opened in 2015. The third floor had been boarded up, thanks to a prior landlord who didn’t want to bother getting the space up to fire code, so for decades the rooms went unaltered or maintained. The GSA worked with a variety of experts and artisans to restore the interior to how Barton would have seen it.

After making your way up the two sets of steep stairs, you’ll find rooms with artifacts telling her story, as well as Barton’s office space, fully recreated. Light fixtures, safely electric, were chosen to recreate the look of gas fixtures that would have been used. And one fascinating aspect of the museum is its walls: The wallpaper is period-appropriate because a design firm was able to take remnants from the uncared-for space and recreate the patterns on them as fresh wallpaper fabric.

In a city where so many museums have an outsize presence on the street and offer impressive art and history, it’s worth taking the time to visit a much more modest space that tells the story of how one woman made a difference for the nation.

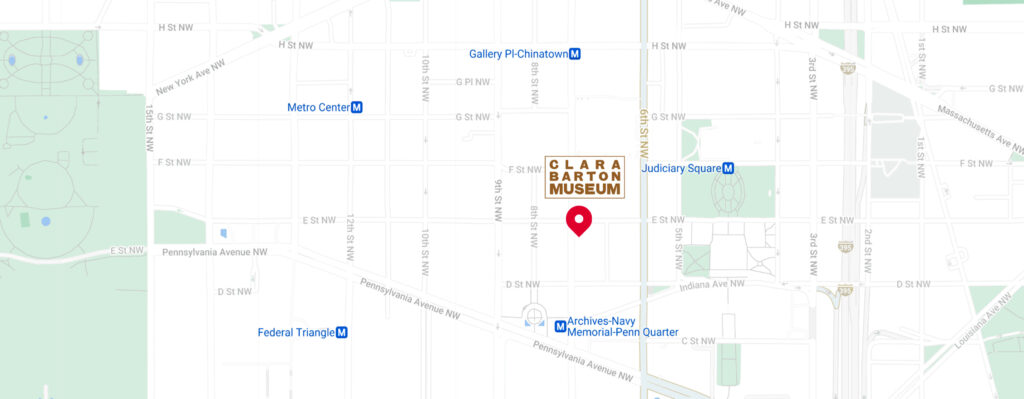

The Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum is located at 437 7th Street NW and is open from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Fridays and Saturdays. All other times, the museum is open to group tours of more than 10, with a reservation. Admission is $7-$9.50 and free for children 9 and younger.